|

Golden Fleece Counterstamps |

|||||||||

|

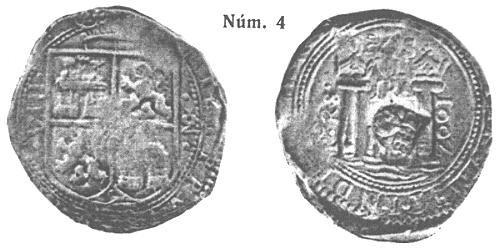

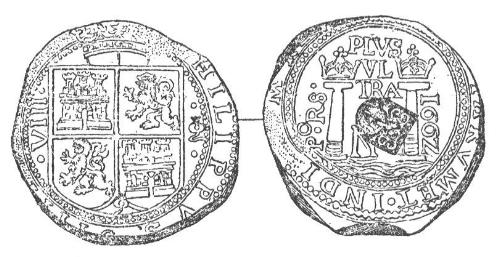

I went to the British Museum in January 2001 to study silver cobs from the Colombian mints of Nuevo Reino and Cartagena, cobs are a crude style of hand hammered coins made in Spain and Spanish America. While looking through trays of coins I came across some Spanish cobs with a Golden Fleece counterstamp applied to them. The coins were properly identified as issues of Brabant. This triggered an association in my mind as I recalled references to a Golden Fleece counterstamp on a Nuevo Reino cob, a photo of one is in Restrepo/Lasser, coin M46-40[1]. Below is an image of another Nuevo Reino coin from the 1914 edition of Herrera’s El Duro[2]. The coin was also illustrated as an engraving in the April 1901 edition of the American Journal of Numismatics[3], more on that further in this article. |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

Catalog References to Brabant

Counterstamped pieces The Spanish and Spanish American coins with the Golden Fleece counterstamps are cataloged in Delmonte[4] as number 324, includes 8 reales, 4 reales and 2 reales. J.R. de Mey[5] assigns catalog number 255 to 8 reales and doesn’t mention 4 or 2 reales. |

|||||||||

|

The counterstamps beg the

questions, “Who, what, why, where and when?” WHAT is the

counterstamp? Some background, this design is the emblem for the Order of the Golden Fleece, an order of knights created by Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy, in 1430. According to Greek mythology, the golden fleece is the sheepskin that Jason and his Argonauts, aboard the ship Argo, searched for and found. The idea is that the fleece represents courage and boldness, suitable for knights. The fleece is suspended from a “fire-steel”, in the shape of the letter B for Burgundy. To understand how the Golden Fleece design came into being it is necessary to place it in historical context. The history of Brabant, Burgundy and France is much too complicated for expounding here in a brief article, but we can start in the 14th century with claimants to the Duchy of Burgundy in dispute over sovereignty of the Duchies with their cousins, the reigning Kings of France. On 6-September-1363, King John II of France granted the Duchy of Burgundy to his fourth son, Philip. John’s eldest son inherited the crown as Charles V of France. During the next 50–60 years there were power struggles between the Dukes of Burgundy and the French crown, out of these rivalries we see the establishment of the Order of the Golden Fleece[6]. How did the emblem of the Golden Fleece itself come into being? I designed to find out and my search lead me to the catalog produced for a museum exhibit in Brussels, 1996. A wealth of information on the Order of the Golden Fleece is in the book and as it is published by the Royal Library of Belgium, I believe the information is reliable. The catalog is entitled L’ordre de la Toison d’or, de Philippe le Bon à Philippe le Beau (1430-1505): idéal ou reflect d’une sociéte? In English the title translates, The Order of the Golden Fleece, from Philip the Good to Philip the Handsome (1430-1505): ideal or reflection of society? The next generation after Charles V of France and Philip the Bold of Burgundy, saw increased hostilities among the key participants in the power struggle. Charles the VI succeeded his father Charles V as King of France, but with his recurring insanity the cousins contended one with another for power. Philip the Bold’s son, John the Fearless was enemies with his cousin Louis of Orleans, brother of Charles VI. The struggle between John the Fearless and Louis of Orleans is a good place to start with the emblem of the Golden Fleece. During that time in history it was common to take emblems and mottoes to represent oneself, and as a symbol of affiliation with some one more powerful. To a degree we still do this today, consider military patches and medals. The importance of these emblems and mottoes must not be overlooked or we will miss the understanding of the Golden Fleece emblem. Louis of Orleans took as his emblem the figure of a knotty stick, or club. To this he added the words “ie lennvie”[7], which translate roughly as “I Annoy It”, referring to the Burgundians. Not to be intimidated or out done, John the Fearless counters this motto with one of his design. In 1405 John chose a carpenter’s plane as his emblem and added the words “ik hovd”, which translates roughly as “ I Hold It”. The plane is in the shape of a horizontal “B” and is shown in motion with wood chips flying, symbolizing the shaving down of the knotty stick of his opponent Louis.[8] The conflict among the cousins escalated with Louis being murdered in 1407 and John the Fearless assassinated in 1419, all of these events drew the participants into the 100 years war, which is another story. Philip the Good inherited the Duchy of Burgundy and immense other territories that his father John the Fearless had built up. He took his father’s emblem of the plane and converted it to a “fusil” or fire-steel, a good translation would actually be lighter, a device still used for starting fire. The fire-steel is operated by putting two fingers through the loops of the B and holding the flint in the other hand. Philip’s emblem is more aggressive and dangerous than the plane of his father, as the fire-steel launches sparks instead of wood chips. To the emblem he added the words “ante ferit quam flamma micet” which roughly translates as “it strikes before bursting to flame”[9]. Philip developed his emblem / motto in 1421-2. It was in 1430, some sources say 1429, that Philip the Good established the Order of the Golden Fleece. For the order he chose his personal emblem, the fire-steel in the shape of “B” for Burgundy, placed two of them back to back and suspended the fleece from a flint stone positioned between the fire-steels. The emblem of the Golden Fleece and the Collar of the Golden Fleece have been used on thousands if not millions of coins in the last 500 years, it is by far one of the most familiar designs on Spanish coinage. Even though it is familiar, the origin of the design itself is not well known, at least it wasn’t to me. |

|||||||||

|

The counterstamps are small and difficult to see, so to better see the fire-steel design. I have reproduced here another image taken from a Spanish Netherlands 1655 Patagon of Philip IV. |

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

Image used with permission of Gary West |

|||||||||

|

WHO applied the

counterstamps? The counterstamps where authorized by officials of Philip IV of Spain. Spain’s claim to the Southern Netherlands, including Brabant and her association with the Order of the Golden Fleece go back to Maximilian I, of the house of Habsburg. Through political agreements, Maximilian’s, father Frederick III, arranged the betrothal of Maximilian to Marie of Burgundy, daughter of Charles the Rash, sometimes called Charles the Bold, (son of Philip the Good and great grandson of Philip the Bold mentioned earlier). The accounts that I read say that the children were attracted to each other and it was an affair of the heart as well as political. It was a complicated and long political affair that looked as though the betrothal would never consummate in marriage. It was only after Charles the Rash died in battle against the French in 1477, that Marie and Maximilian were wed, even then Marie and her mother Margaret of York had to make skillful negotiations to deny competing French aspirations to marry Marie to Charles, son of Louis XI. This marriage, which brought wealth and additional power to the Habsburgs, forever changed the course of European history. For further information see Crankshaw[10]. Through Maximilian’s marriage to Marie, the house of Habsburg inherited Burgundy and the Grand Mastership of the Order of the Golden Fleece. When Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire ( not to be confused with Charles V of France), grandson of Maximilian, retired in 1556, he divided his dominions, into two parts, with claims to Germany, Austria and the Holy Roman Empire going to his brother Ferdinand; Spain, the Spanish Netherlands, the New World and more going to Charles’ son, Philip II. This division took two years. It is from this division that Spain held claim to the Spanish Netherlands and that the Order of the Golden Fleece later split into two branches, the Habsburg and Spanish branches. The Grand Mastership of the Spanish branch is today held by King Juan Carlos. WHERE? The coins were counterstamped in the Spanish Netherlands, the Brabant region including Brussels in what is today Belgium. WHEN and WHY? It looks as though there were a great number of Spanish coins circulating in the Spanish Netherlands during the middle part of the 17th century. Part of this money was to finance the Army of Flanders during the Thirty Years War[11]. A great number of these Spanish coins were cobs and a lot of the cobs were found to be underweight and low purity, likely related to the mint scandal at Potosi which led Philip IV to order a complete redesign of the coins (to the beautiful pillars and waves design) produced in South American mints. Also the practice of clipping, or trimming of metal along the coin edge was responsible for some light weight coins. In section nine of Philip IV’s pragmatica of 1-October-1650, he specifically banned counterfeit coins that originated in France and Portugal as distinct from the spurious coins originating in Peru, which were recalled[12]. In order to reduce fraud and facilitate commerce the government required all Spanish cobs to be turned in to the mint for melting and made into new money. In areas were there was no mint, certain money changers were authorized to test the cobs, and if they determined the coins were of proper weight and fineness to counterstamp them with the Golden Fleece. This practice began in 1652 and ended approximately 1672 when the government “discovered” that the people were clipping the counterstamped coins and so even though they were stamped as proper weight, they had now become adulterated and hence the stamp was no longer a reliable indicator of full weight coins[13]. As well as clipped coins there were possibly counterfeited counterstamps as well[14]. With thanks to Brunk and previous generations of numismatists, we today have information that could otherwise have become lost or so obscure as not to be identifiable. Gregory G. Brunk compiled an anthology of articles concerning countermarks on coins in his World Countermarks on Medieval and Modern Coins[15]. In it he reprints an article from the April 1901 edition of the American Journal of Numismatics entitled Counterstamps on Spanish and Spanish-American Coins. The Journal article in turn was a reprint and I assume a translation, of an article printed by Alphonse DeWitte in the Revue Belge. In that article was a quotation from an official announcement, bill or placard which is highly informative, the announcement was printed in 1652 at Antwerp. The quotation below is from the 1901 Journal. |

|||||||||

|

TOUCHING SPANISH REALS “It has come to our knowledge that among the above-named Reals – the whole pieces called Mattes, and the parts thereof, halves, quarters, eighths, and sixteenths, - it is found on assaying them, that a great number of those from Peru and other places have been adulterated, counterfeited, or are not up to standard in alloy or in weight, so that the public are unable to value them at their actual worth and it is also difficult to discern the good from the bad: for this reason we have, in the past, and do now declare them base; and further, as the Reals of Spain and Mexico, which have circulated among the people for forty, twenty, ten, and two-and-a-half pattars, are all too light in weight, we do ordain that they shall be brought to the mints, or to the sworn money-changers, so that the value thereof may be determined according to assays which shall be made; and the better to discern between the Reals of Spain and Mexico (of just weight and alloy) and those of Peru, we further ordain that before it be permitted to put them in circulation they shall be carried to our mints as aforesaid; or in places where there are no mints, to the sworn moneyers, there to be marked with punches prepared for this purpose, under penalties set forth in these placards. “Reals of Spain and Mexico being counter marked with this device may be allowed to circulate as of the value of forty-eight pattars.” |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Also, shown below from the 1901 Journal article is an engraving of the same 1662 eight reales which is photographed in Hererra 1914 featured at the beginning of this article. | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

The Brabant Counterstamped

pieces in the British Museum I found four counterstamped Spanish cobs in the British Museum coin trays, as listed below.

|

|||||||||

|

How does a fire-steel work? To make fire with this device you need three things; flint, tender and steel, the harder the steel the better. By striking the steel against the flint, pieces of the steel are abraded and this causes sparks, the sparks must be directed into the tender to set the tender aflame. |

|

||||||||

|

Thanks to Curator Helen Wang and museum assistant Ian Lewis for their generous assistance during my inspection of the collection and providing reference books from the department’s library. A special thanks to Janet Larkin who also assisted me and arranged for the photographs. For reference, the web site address for the British Museum is http://www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/ Thanks also to the following persons for their assistance in my research: Dr. Barrie Cook, British Museum, Curator of Medieval and Early Modern Coins; Philippe Elsen of Jean Elsen Numismates; Nicholas C. Seijffardt at Simtom.marketing@pandora.be; Jane Colvard at the ANA library; Gary West of Colonial Era Coins for use of his image; and to the NI librarians Granvyl Hulse and Jim Haley. All rights reserved by author, Herman Blanton. Any publication rights are given non-exclusive only. Images of coins in the British Museum Collection are not reproduced as I do not have rights for electronic publication, to see images of two pieces refer to the NI Bulletin, Volume 37, Number 1, pp. 6-15, January 2002 edition; a printed publication of Numismatics International, Dallas, Tx.. To the best of my knowledge the images from Herrera and The American Journal of Numismatics are in the public domain. |

|||||||||

| References. | |||||||||

|

[1] Jorge Emilio Restrepo and

Joseph R. Lasser, Macuquinas de Colombia, (The Cobs of Colombia, South

America (Medellín

Colombia: private printing, 1998) p. 27. [2] Adolfo Herrera, El Duro (Madrid: J. Lacoste, 1914) Vol. I p. 236 and plate XVIII. [3] Editor, “Counterstamps on Spanish and Spanish American Coins,” American Journal of Numismatics, Vol. XXXV-No. 4 (Boston: April 1901): pp. 103-104. [4] A. Delmonte, The Silver Benelux (Amsterdam: Jacques Schulman N.V., 1967) pp. 82-83. [5] J.R. de Mey, Les contremarques sur les monnaies (Brussels: Numismatic Pocket, 1982), pp. 41-42. [6] Guy Stair Sainty, The Most Illustrious Order of the Golden Fleece, [ Online. Internet. 27 February 2001. Available: http://www.chivalricorders.org/orders/other/goldflee.htm ] [7] Dr. Michael Pastoureau, “Emblèmes et symbols de la Toison d’or,” L’ordre de la Toison d’or, de Philippe le Bon à Philippe le Beau (1430-1505): idéal ou reflet d’une société? (Brussels: Royal Library of Belgium, 1996), p.106. [8] Pastoureau, p. 106 [9] Pastoureau, p. 104 [10] Edward Crankshaw, The Habsburgs, Portrait of a Dynasty, (New York: Viking Press, 1971) pp. 34-40. [11] Dr. Barrie Cook. 2001. Personal communication. [12] Aloiss Heiss, Descripción General de las Monedas Hispano-Christianas desde la Invasion de los Arabes (Madrid: R.N. Milagro, 3 volumes, 1865-1869), Vol. I, p.350. [13] de Mey p.41 [14] Cook. 2001. Personal communication. [15] Gregory G. Brunk, World Countermarks on Medieval and Modern Coins . (Lawrence, MA.: Quarterman Publications 1976) pp. 164-165. |

|||||||||

| ©Copyright 2001 Herman Blanton | |||||||||